And that was too bad – because it’s not as though racism stopped being an issue in a global pandemic; if anything, as we’ve seen with the stark racial disparities of whose lives are most affected by COVID-19, the killings of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd, and Amy Cooper’s calling of the police claiming that an African-American man was threatening her life, racism is alive and well.

So here is where I turn to fellow white folks in our community. Rather than another round of article-sharing, hand-wringing, and righteous indignation until the next headline comes along, I want to suggest that one of the best responses to feelings of confusion, powerlessness, and anger at instances of racial injustice is to join with others in our spiritual communities to turn the lens inward, on ourselves, and begin to examine how white supremacy manifests in our own hearts, minds, actions, and communities.

For me, one of the major lessons of JCUA’s racial justice training was the suggestion for us to shift away from talking about racism and move toward an ability to speak about white supremacy.

Why? What’s the difference?

When I think about racism, I imagine acts of hate done by individual racists, consciously. It puts me on the defensive. I’m not a racist, right? If I understand myself as a fundamentally good person, I can’t also understand myself as a racist — it just doesn’t compute.

But when I learn to get comfortable using the language of white supremacy, I realize that it’s not just about white KKK robes, modern-day lynchings, or police brutality. It’s about an entire ideology, on which our nation is based, that white people are superior to people of color. That ideology has been fundamentally baked into our schools, our police forces and prisons, our housing policies and healthcare — and has found its ways, insidiously, into our own minds and hearts.

Growing up in public school classrooms in South Carolina, I sat in honors classes that were predominantly white and subconsciously reasoned that this was because white kids were inherently smarter than black kids; I had no understanding of unequal access to key educational resources, like quality curriculum, skilled teachers, family support or financial stability. I just accepted this “truth” as a given throughout my childhood and early adulthood, and it was only through reading and attending trainings such as JCUA’s over the past decade that I could begin to unlearn the tenets of white supremacy that I had unwittingly absorbed from such a young age.

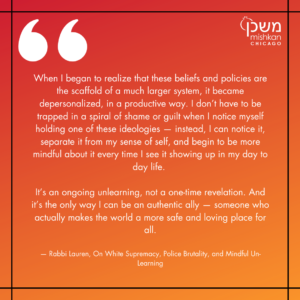

When I began to realize that these beliefs and policies are the scaffold of a much larger system, it became depersonalized, in a productive way. I don’t have to be trapped in a spiral of shame or guilt when I notice myself holding one of these ideologies — instead, I can notice it, separate it from my sense of self, and begin to be more mindful about it every time I see it showing up in my day to day life. It’s an ongoing unlearning, not a one-time revelation. And it’s the only way I can be an authentic ally — someone who actually makes the world a more safe and loving place for all.

This is the approach I try to practice when I see manifestations of white supremacy pop up in my community. Of course, when I hear someone say something racist, my first reaction is to get angry and pounce. But though immediately calling them out and shaming them will feel righteous, momentarily, I know it isn’t going to lead to deep, lasting change for them, or for me. So I try the zoom-out approach, naming and noticing the belief, questioning it, pointing out how it is rooted in an ideology of white supremacy, and sharing how I’m in my own process of un-learning this too. As a white woman, this kind of patience is a privilege. A privilege because when someone says something racist in my presence, there is no immediate threat to my physical well-being — I have the privilege to zoom-out, the privilege to take a breath, and move forward without conjuring years of racial trauma. And that privilege can be in service. I can use my voice, a voice that hasn’t been exhausted by years facing racism, to speak up and help guide another’s un-learning.

On the eve of Shavuot, as we open to the experience of revelation of Torah, this approach to learning and unlearning reflects our Jewish tradition’s understanding of how the process of revelation itself occurs: not as a one-time event in history, but as an ongoing process. When Moses recaps the memory of revelation at Mt. Sinai for the Israelites in Deuteronomy, he says, “The LORD spoke those words—those and no more (velo yasaf)—to your whole congregation at the mountain, with a mighty voice out of the fire and the dense clouds,” (Deut. 5:19). Rashi picks up on the phrase “velo yasaf” and says this means that the Divine voice speaks without needing to pause, as humans do, and therefore God’s voice continues to reverberate today.

Our job is to pick up on those echoes of divinity and answer their commanding presence – to hear the call to unlearn patterns of oppression and replace them with a vision of humanity that recognizes the divine spark that exists in every single human being. I would argue it is not just a moral obligation – it is a spiritual one.

I need to dig deeper, slow down, and allow myself to be honest with me, first and foremost— thank you for this “revelation”!

I can relate to your journey. Thanks for sharing. The idea that “good” liberal minded people still hold many racist beliefs was a game changer for me. Being able to sit in that fact and work through it is the work that needs to get done to heal and activate change. I am still growing and learning (or unlearning as you put it) and am grateful to be able to read thoughts and ideas from others on this self discovery path. Thanks again.

Thank you for writing this piece. It resonated with me an my life experiences, not because they were similar to yours, but because they were somewhat OPPOSITE of yours, albeit I am soon to turn 77, so our generational differences speak volumes. I grew up in a northern city with a large Black population and with a city government loaded with Socialists at the time. Our schools had “Sister” and “Brother” schools wherein we shared events with other schools in the hopes that the races would communicate and become friends. It never entered my mind that Blacks were not as bright as I was, that many were brighter or more able than I. It was obvious when we jointly attended each other’s events, basketball games, debates, plays, etc. My father was the principal at a racially mixed elementary school and I would visit the school on weekends when he had to to into school for some business or another. When I saw what kind of lessons the kids were undertaking, I never saw, or didn’t see, any difference in what I was learning and what they were learning. My mom taught me that if I had a problem on the bus going to or from my cello lessons downtown, I was to ask a Black person for help. She said that “they” would know what to do and that I would be safe. I guess it created a certain mindset in me that later, has caused me great distress in viewing the pains suffered by racial minorities. It is probably why I spent my career working in Native American villages in Alaska. As an adult, I came to realize the reason WHY the Black kids were primarily at certain schools — defacto segregation. All of this gets down to education at home and in school. Lately I have been reminded of a song from the play, “The King and I”. It sums up so much of what I have always believed was a major root of discrimination. Maybe I am wrong. Maybe not. Bless you for your work and especially your work with the younger generation around you in Chicago. As a funny end to this diatribe, my father used to drive down to Chicago to buy bootlegged marjarine and drive a trunk load of it up to Milwaukee for his teaching staff. (early 1950s) But back to The King and I. Here is the song:

“You’ve got to be taught

To hate

And fear

You’ve got to be taught

From year

To year

Its got to

Be drummed in your dear little ear

You’ve got to

Be carefully

Taught

You’ve got to be taught

To be

Afraid

Of people

Who’s eyes are oddly made

And people who’s skin is a different shade

You’ve got to

Be carefully

Taught

You’ve got to be taught

Before it’s too late

Before you are six

Or seven

Or eight

To hate all the people

Your relatives hate

You’ve got to

Be carefully taught

You’ve got to

Be carefully taught”

“You’ve got to be carefully taught” is from “South Pacific”, 1958. The anti-prejudice song from King and I might be “Getting to Know You” but it lacks the truth and power of the South Pacific song. For years, I’ve maintained that South Pacific should be required watching and presenting in High Schools.