This drash was given by Rabbi Lizzi Heydemann on March 11th, 2022. You can listen to the full sermon on Shabbat Replay on Contact Chai.

As the full moon rises, Jews all over the world will gather to celebrate the fun and singularly bizarre holiday of Purim. We will show up in costumes and masks (the kind of masks that you would have thought of before a global pandemic) to eat and drink and hear the Megillah, The Book of Esther, from a handwritten scroll on parchment. And if you’ve ever been to a Megillah reading before, then you know it’s not like attending a docile poetry reading or book talk. It’s more like attending a midnight viewing of Rocky Horror Picture Show or watching Frozen with anybody born after 2009. It’s a participatory experience! There are lines that you read or shout along with the person who’s reading. And of course, we boo whenever we hear “Haman.”

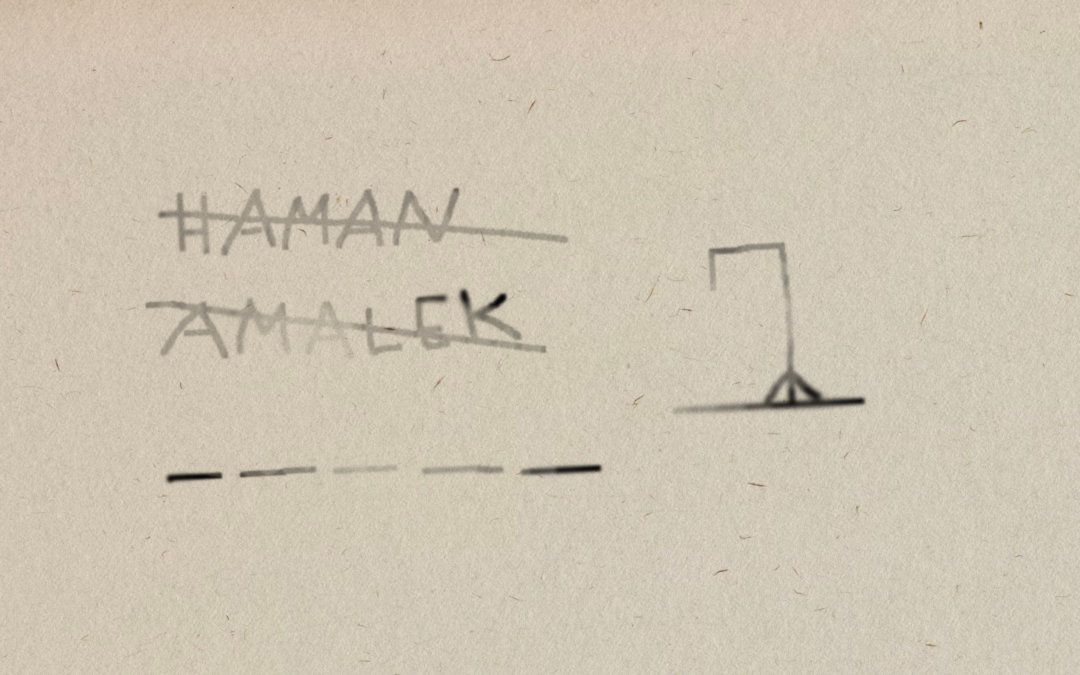

Blotting out the name of the villain is not just Purim theatrics. In more observant circles, when someone says the name of any evil person from history, they often follow up by saying “Yimakh shemo,” or “may his name be erased.” But wait, if you are trying to erase someone’s name, why say it at all? It’s a bit of a paradox, one which is lifted up in the reading that we do every Shabbat before Purim.

This Shabbat has a name, Shabbat Zachor, which means the Shabbat of remembering. And it’s not just thematic — it’s named for a particular verse in the Torah. Moses is giving his last instructions to the Jewish people before they go into the land of Israel. These are the children of the people who walked out of Egypt who God deemed unprepared to enter the Promised Land. That includes Moses, by the way, so he’s trying to tell them as much as he can, knowing that he’s not going in with this new generation. So he says to them, “Remember what Amalek did to you on the road out of Egypt. How undeterred by fear of God! He surprised you on the road when you were hungry and tired and cut down all the stragglers at the back of the line. And so, when God grants you rest from all your enemies around you in the land that God is giving you as an inheritance, you will block out the memory of Amalek from under the heavens. Don’t forget!”

So who is this Amalek we are supposed to be forgetting? Basically any evil character who comes to pursue the Jews at any point in history is called a descendant of Amalek by the sages. But where does Amalek start? Amalek starts in the Torah as a marauding band of warriors that attacks the Israelites as they’re leaving Egypt. As the text says, they pick off the old and the weak and the infirm and the people who are at the back of the line. They’re cruel and inhumane. Moses tells the children of the people who survived this attack that they must erase the memory of this Amalek that they paradoxically also must not forget.

What do we do with this? Much Jewish commentary ink has been spilled over this question. My grandma Alice escaped Nazi Germany. When she came to America, she did not talk about what she went through. Many families share that story. They started new lives in safe places and tried to erase the memory.

Remember and forget — a moral binary, apparent opposites. The art of a Jewish spiritual life is knowing when to apply which strategy.

There are many Jews whose identities are staked on the first part of that equation: “remember.” The recent Pew study done in 2020 said that 76% of American Jews believe that remembering the Holocaust is an essential part of what it means to be Jewish. That was the highest percentage of Jews agreeing on anything! And for many of these Jews, remembering the Holocaust is not just a matter of looking at our history of oppression. It’s knowing that it’s just a matter of time before Amalek rears his ugly head again. Rabbi Sid Schwartz calls this kind of Jew a “tribal Jew.” And he doesn’t mean that in a pejorative way. This descriptor reflects the fact that many of us understand the world through a lens of the historic persecution of our tribe. People attacked us for no reason other than our being Jewish. Therefore, we need to rely on only ourselves for survival and for protection, because when push comes to shove, no one else will be there for us when we need them. It’s not an unreasonable thing for a person to think. However, when our identity as Jews is grounded primarily in remembering a traumatic past, this leads to living in the present with a constant low-grade anxiety, a paranoia that we are constantly about to be slaughtered. But that cannot possibly be true all the time, and it affects our judgment and wellbeing in the meantime. We don’t make good decisions from a place of fear.

Rabbi Schwartz talks about another kind of Jew: the Covenantal Jew. A Covenantal Jew stakes their identity not on history so much as social responsibility. They believe in a covenant between the Jewish people and a higher power that obligates us to heal the world. According to the Pew report, 72% of Jews in America agree on ethical and moral action as being an essential part of a Jewish identity. Most people are some combination of both Tribal and Covenantal. Like Moses’ remember/forget binary, this one’s false, too!

The question is not, “Should we worry about ourselves?” Of course we should worry about ourselves! Our tradition is right to emphasize this point. But it’s also necessary for us to use our tradition’s moral imagination to care for the health and welfare of the people around us.

Purim is a blueprint for doing this. We can hold both the remembering and the forgetting, the tribal and the covenantal. Purim shows us how to remember our history of victimhood without letting it limit our actions in the present and then actually leverage that painful past on behalf of others.

We are given four mitzvot to uphold in keeping this ingenious holiday:

- Hear the Megillah.

- Have a feast.

- Give gifts of food to people you love.

- Give generously to the needy.

Of course, some people say there are actually five mitzvot, because you’re supposed to party both in the evening and in the morning. All that partying might lead you to make the mistake of thinking that Purim is a frivolous occasion. But people who call it “Jewish Halloween” are missing the deeper reason why people created this holiday. And if you read the story, you’ll see that it’s people who created this holiday; God doesn’t even appear in the Purim story! Scholars consider Esther a biblical farce, like a Saturday Night Live sketch playing off of the fears and anxieties and fantasies of Jews in the ancient world. So you get sex and drugs and partying and genocide and revenge and power. You get male insecurity paired with female power. These juxtapositions are delightfully funny, but they also invite us to hold the messy contradictions of life with joy.

Purim shares a name with Yom Kippur: Yom ha-Kippurim. Which is weird, because Yom Kippur is opposite on the calendar and in practice. But ultimately, both holidays are about reckoning with the fact that we don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow. The world can turn upside down in an instant. A few weeks ago, the world changed in ways nobody could foresee. Who could have predicted that states would be rolling back rights for women and LGBTQ+ and trans people in 2022? Or the war in Ukraine? You wake up one morning and the world is a different place. On Yom Kippur, the answer is: “Life is short and we don’t know what tomorrow brings, so fast, forgive, and apologize.” On Purim, the answer is: “Life is short and we don’t know what tomorrow brings, so eat, drink, and be merry!” The genius of the Jewish calendar is that these extremes on either pole show us how to live the rest of the year navigating the gray.

The rabbis of the Talmud say that one day, when the Messiah comes, when we’ve all done our homework and so totally transformed the world that Amalek has been erased from the planet, Purim will be the only holiday we still celebrate. Why Purim? I think one reason might be that this holiday encapsulates the whole Jewish tradition. The story and mitzvot of Purim are a rubric for an integrated Jewish identity, one that holds onto the past but isn’t defined by it. That is our people’s alchemy: taking the pain of our story and turning it into a blessing for the whole world.