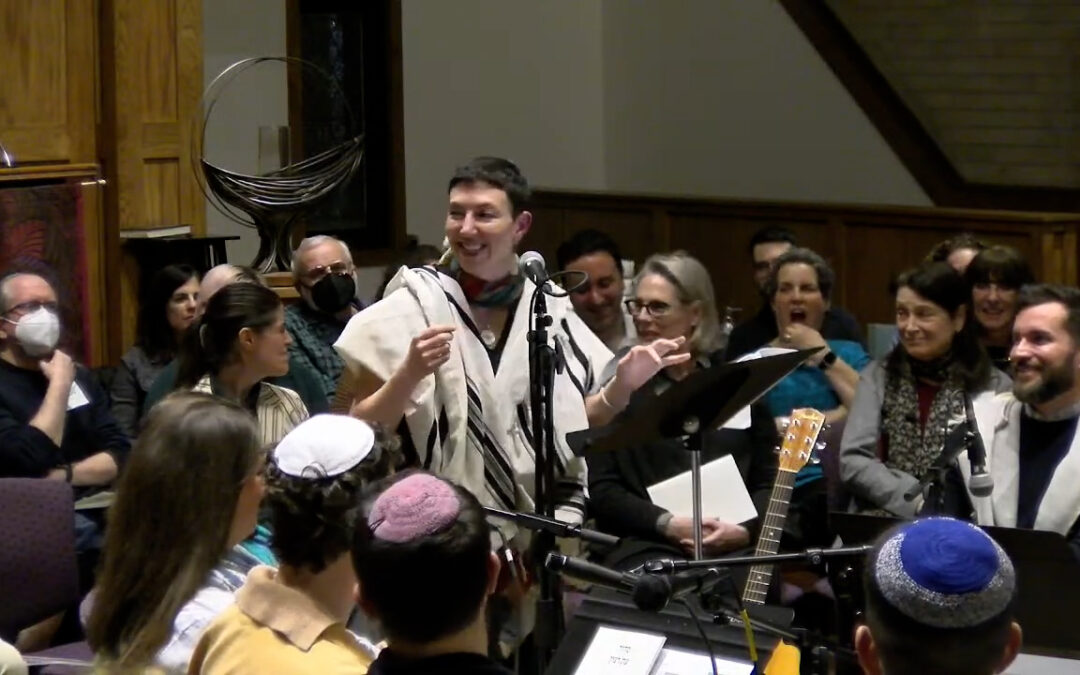

After a well-deserved sabbatical, Mishkan’s founding rabbi took to the bimah at our February 9th Friday Night Shabbat service. In a wide-ranging sermon, Rabbi Lizzi addressed the ongoing Israel-Hamas war and called on all of us to do the difficult work of believing that a peaceful future is still possible. You can listen to this sermon on the latest Contact Chai podcast or watch on Mishkan’s YouTube channel.

****

As we turn in our davening to Hashkivenu, the prayer that asks that we lie down in peace and be raised up again to life, I want to pray for peace in this city. For our brothers and sisters in this city, for kids in this city. And I want to specifically tonight pray for Jewish kids, including college kids.

This week, as you may have heard, the Hillel building at Loyola University was defaced with a swastika, the most recent antisemitic incident here in Chicago. It’s almost too much to keep track of, to mention week to week, and yet we have to acknowledge that this is happening. This is happening in 2024 in America, in our city.

So much of our world right now is shaped by fear, the fear and ignorance that drives hate, and the fear we feel in response to a world that feels increasingly hostile towards our presence. I’m not talking about people protesting a particular policy of Israel, though that can often veer into antisemitism, I’m talking about acts and words that target Jews, like a swastika on a Hillel, or like a stranger slapping the kippah off the head of a Jew in the street.

I don’t know about you, but this was not part of the landscape of my childhood. I remember this one time as a kid, I was wearing a Star of David I got for my bat mitzvah, my Dad told me to tuck it in as we got on the airplane. I thought, why? Answer: all these people don’t need to know you’re Jewish. And I remember thinking how silly that was, how safe I felt, how I didn’t need to hide. Not true anymore for Jewish kids.

I want right now to pray for Jewish kids who don’t know what to make of what’s happening around them right now, for their parents, and for us, who are having a hard time figuring out how to talk about it. I want to pray for teenagers and college students to have the strength of identity to be proud of who they are, and never feel like they have to hide.

This song, Acheinu, is that prayer. I also want to ask us who tonight we’re praying for, for their healing and recovery, and hold them as well as we pray for our siblings and friends.

May this be the case for us, and for all kids, wherever they are.

****

A few of you said to me over the course of this week: a lot is riding on this Friday night. People are listening. People want to know what you have to say after three months away.

No pressure.

Last week’s Torah reading described all Jews and all non-Jews that escaped Egypt with them, adults and children, men and women, every body, standing at Sinai receiving Torah together. And in one of my favorite bits of midrash, we are told that all 2 million-ish of these people had their own vantage point and way they internalized the message. This person was shorter, this one taller, this one in a wheelchair. Children might have heard it in the voice of their parents. Adults in the voice of their lover. Elders in the voice of their deceased partners. Blind or deaf — it didn’t matter, they experienced the revelation according to their own life experience and ability. God, we are assuming, knew this variation was taking place. She’s the Creator of the Universe after all, if she’d wanted everyone to experience the same thing then they would have. But apparently even 4,000 years ago in Torah, or 2,000 years ago in Midrash, our ancestors understood that different people respond differently to what’s right in front of them, and nonetheless, must build community together in the presence of those differences.

And this week, we go from the sublime divine experience of revelation — the thunder and lightning and shofar blasts and awesome terror of Sinai — to a Parasha whose name is “laws,” Mishpatim. It’s still part of the revelation, but man, instead of doing shrooms it’s more like pulling a torts law book off the shelf. After the 10 commandments of last week, this week it’s hundreds of laws spanning the gamut of scenarios describing how to create a new and visionary Israelite society for these freed slaves.

Some of our best and most powerful ideas are in this week’s reading, hidden in tort law. So for example this week, right now, it’s Repro Shabbat, the week Jews across America affirm our commitment to the right to reproductive healthcare, including abortion. Jews, the world over for thousands of years, have been pro-choice. Why? We debate everything. Why isn’t our internal debate about abortion as polarized as the one in America?

Well, in this week’s Torah reading we learn what happens in the awful case of a pregnant woman getting pushed, and miscarrying. The guy who pushed her, owes her family money. However this is in contrast to if he kills or injures her body, in which case, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, life for life. The rabbis of the Mishna and Talmud look at this and say, aha, if you kill a live person, for example a pregnant woman, the offender is liable for her life. But if she miscarries the fetus, you’re only responsible to pay for damages. Therefore, a fetus must not be considered a life until birth. Period, end scene. We don’t encourage abortion, however we don’t consider it to be murder.

Different sects among our people deal differently with the question of all manner of reproductive health care, but at the end of the day, Judaism is a pretty sex-positive, pro-choice religion, on the whole. For all that the Torah is archaic and has a lot that needs reinterpreting, I’m always astounded and grateful for the places where Torah is more progressive than our own modern political landscape.

Not the direction you expected me to go tonight, is it? Don’t worry, I got more directions.

I wanna read you a few more classic verses from this week’s Torah portion, because otherwise you won’t hear them, and I want you to hear them. (I’m leaving out a LOT of good stuff);

From Exodus 22:

כׇּל־אַלְמָנָ֥ה וְיָת֖וֹם לֹ֥א תְעַנּֽוּן׃

You shall not mistreat any widow or orphan,

אִם־כֶּ֣סֶף ׀ תַּלְוֶ֣ה אֶת־עַמִּ֗י אֶת־הֶֽעָנִי֙ עִמָּ֔ךְ לֹא־תִהְיֶ֥ה ל֖וֹ כְּנֹשֶׁ֑ה לֹֽא־תְשִׂימ֥וּן עָלָ֖יו נֶֽשֶׁךְ׃

If you lend money to the poor among you, do not act toward them as a creditor; exact no interest from them.

Chapter 23:1-5

לֹ֥א תִשָּׂ֖א שֵׁ֣מַע שָׁ֑וְא

Don’t carry false rumors;

לֹֽא־תִהְיֶ֥ה אַחֲרֵֽי־רַבִּ֖ים לְרָעֹ֑ת וְלֹא־תַעֲנֶ֣ה עַל־רִ֗ב לִנְטֹ֛ת אַחֲרֵ֥י רַבִּ֖ים לְהַטֹּֽת׃ וְדָ֕ל לֹ֥א תֶהְדַּ֖ר בְּרִיבֽוֹ׃

You shall neither side with the mighty to do wrong— nor shall you show deference to a poor person in a dispute.

כִּֽי־תִרְאֶ֞ה חֲמ֣וֹר שֹׂנַאֲךָ֗ רֹבֵץ֙ תַּ֣חַת מַשָּׂא֔וֹ וְחָדַלְתָּ֖ מֵעֲזֹ֣ב ל֑וֹ עָזֹ֥ב תַּעֲזֹ֖ב עִמּֽוֹ׃ {ס}

When you see the ass of your enemy lying under its burden and instinctively you would refrain from raising it, you must nevertheless help raise it with him.

Exodus 23:8-9

וְגֵ֖ר לֹ֣א תִלְחָ֑ץ וְאַתֶּ֗ם יְדַעְתֶּם֙ אֶת־נֶ֣פֶשׁ הַגֵּ֔ר כִּֽי־גֵרִ֥ים הֱיִיתֶ֖ם בְּאֶ֥רֶץ מִצְרָֽיִם׃

You shall not oppress a stranger, for you know the feelings of the stranger, having yourselves been strangers in the land of Egypt.

That last one’s repeated 36 times in the Torah.

Nice to be brought back to some of the touchstones of what makes Judaism interesting, profound, complex, challenging, right? That’s why I became a rabbi. To learn and share Torah.

But if you heard the sermon I gave right before I left — as I stood here at the end of October — I’ve really been questioning, what is the role of a rabbi right now? Do I even want to be a rabbi anymore? It doesn’t feel like it’s about teaching Torah anymore. It seems to be a combination of being an emotional first responder, as well as a public relations or marketing professional. Tending to the wounded, to the traumatized, and also saying just the right words so that the fewest number of people write angry emails and tell you you are siding with the wrong victim. Do you know what I’m talking about? And these two jobs often play off each other.

And you don’t have to have known someone who died or was kidnapped on October 7th, or for that matter, you don’t have to know someone in Gaza, to be traumatized by what happened, and what has happened since October 7th. Our people always carry with us some amount of latent generational trauma, it’s part of our core narratives, from Passover to Purim to Tisha B’Av to Auschwitz… the story of persecution and oppression wherever we’ve gone. But now, even as we sit in the midst of a free society, in Chicago, not Israel, events like October 7th bring it up from latency to the surface and we begin acting and responding from that place of trauma.

Often the first thing to go when we feel stressed and under attack is our breath, so I want to invite you now to take a deep breath. The Torah describes that the Israelites couldn’t hear Moses offering them a way out, because they were kotzer ruach, because of shortness of breath.

When we are operating from a place of trauma, we often see real threats — that’s what we’ve evolved to do — but we also become hypersensitive to perceived threats that may or may not be real, say, in a newspaper article, or our Mishkan emails or your rabbi’s sermon. Suddenly even the spaces we felt safe and good a few weeks earlier, we wonder now, is this place safe for me? Safe for me to love and bleed for our Israeli brothers and sisters, without equivocation, which I do? Yes, it is safe here. Or safe to say, we don’t want Gazan children to pay the price for Hamas’s war, which I don’t. Yes, you’re safe here. When we’re operating from trauma, our defenses go up, and sometimes we’re suspicious of the motives even of our friends, and even of communities we’ve been part of for years. It hurts everyone in the situation.

Given all the community trauma, some folks asked whether the timing of my sabbatical should be rethought. I said Hamas has already done enough damage: they don’t get to destroy my sabbatical too. And also, I had a feeling the same issues would be here when I returned.

And indeed they are, but they’ve shifted. For example, back in October and November there was no appetite in Israel to not respond to Hamas’s egregious, brutal, horrific attack with massive force, and to suggest as much from over here sounded like it was telling the world’s only Jewish state, attacked for being a Jewish state, that it didn’t have the right to self-defense, which it does. However, as Rabbi Doniel Hartman — an Israeli rabbi and thought-leader, said last week — for people calling for Hafsakat Esh, ceasefire now, many of them are the families of hostages being held in Gaza, and who know that with every passing day of the war, their return becomes less and less likely. You cannot accuse the families of the hostages of being anti Israel for wanting a ceasefire.

Shoshanna Cohen, a Fellow from the Hartman Institute, mused yesterday as she taught a group of us rabbis, at how strange it is that fighting for the hostages to return in Israel is a lefty cause and here it means you’re on the right. What’s up with that, she wondered. And I agree, what’s up with that?

Back in October no one was protesting in the streets in Israel, the whole country was in shock, mourning and grief. Now, the Saturday night protests are back, people are calling for Bibi’s removal, and this past week 30 Israeli organizations came together to call for a Hafsakat Esh, a cease of the fire. In Israel, the landscape has changed and people are looking at the same facts differently. Some of the same people are looking at the same facts now, four months later, differently.

And so are we. Like Sinai was a defining moment for the Jewish people, so is this. And like at Sinai we experienced things differently, and yet were expected to build a society together, in the presence of difference, that’s true here too. At least at Mishkan. I’m incredibly committed to that vision. And while I and other Jewish leaders have been under immense pressure for months. I came back from the sabbatical refreshed and more human, and I looked around at my colleagues and everyone is bone tired, everyone is exhausted to the point of tears, almost all the time. There is so much pressure to have the right message, say the right thing every single week. And many of the people bringing things to sign or say, are making really important points, and sometimes those points are in conflict, but none of the people I’ve talked to are evil or bad or don’t deserve to be in this community.

My first and most important job is to help create a community here that is capable of holding sincerely felt difference in the midst of a heartbreaking situation that threatens to drive us apart from each other.

But just like Hamas doesn’t get to take away my sabbatical, they also do not get to divide us from one another. Then they really win.

As you know I’m going to Israel next week to bear witness, to talk to survivors, to be in solidarity with a people that feels very alone in the world… and I wanted to bring something with me for people who have been displaced from their homes. Our tour guide Karmit, from our 2022 trip, lives in a town in the north that was evacuated, and I sent her a Whatsapp message asking what do you need, what can I collect from my community?

And she said, “Hope.”

She said, people here are so defeated, they don’t believe peace could ever be possible, not now not ever. But 20% of Israel is Arab Israelis, Palestinians, and other non Jewish ethnicities… she said, we have been living together, building together, for decades. There’s a lot of work to do before we can claim that Palestinians in Israel share equally in the bounty of this democracy, but it’s a model for what’s possible, or at least the beginning of what’s possible. But we have lost our faith. So we need you, from the vantage point of where you sit, in a place where people build a society across difference, to remind us that it’s possible. Israelis and Germans drink beer together, marry each other. America and Japan are doing quite well in their relationship. Countries, peoples, that have been enemies, can make peace. But they have to believe it. She said, Please bring hope.

And I know many of you also have lost faith that it’s possible too. From statements from leaders, and charters, calling for the destruction of the other people, there’s a lot working against the idea of hope. And yet, if we can’t imagine it, it’s not possible. And if they can’t imagine it, it’s not possible. I can only go back to being the kind of rabbi I trained in Rabbinical School for, when we harness our hope, and so do they. So we need to. That’s just our job. I don’t see any other way. For anyone who wonders what does Pro-Israel look like? That’s what it is. It’s also Pro-Palestine, for that matter. It’s pro-People in that region figuring out how to live in that region together without killing each other ad olmei ad, til the end of time.

But I believe that we can transcend our trauma for the sake of building a richer, stronger community, a community to ask hard questions ourselves, and it grows through loving challenges. There is now a generation of Israeli and Palestinian children who don’t believe that there is peace to be made, but their minds could be changed by their parents, by what they see, by who they talk to, by organizations that are teaching both the past and the future differently. So I want to ask us, in the midst of a subject that evokes immense stridency (we all become military experts when we talk about this subject), to not live in the conflict today, on Shabbat.

To dream, to imagine a peaceful future. We can hold out that vision, as unlikely as it may feel, we can support organizations and people living that vision — and there are many, and they get nastier emails than I get for their work, which is often considered traitorous, but more importantly, it’s brave. The least we can offer ourselves as bolstering support for anyone who believes in the necessity of building a society alongside people whose experience differs from our own. We as Jews have been doing it a long time. We know it’s possible.

Your question about your rabbinic role is germane, but I’m thinking the answer isn’t dichotomous: teacher of Torah OR trauma counselor/chief marketing officer.

This might be one of those “both-and” moments where looking closely at our sacred texts does, indeed, help us navigate a treacherous path, walking a tightrope while dodging stones and accusations being thrown by partisans on both sides (or all five sides).

I want to be a compassionate humanitarian who helps lift up my enemy’s donkey, even while painfully aware that my enemy’s friends were killing, raping, torturing MY friends. That’s a big ask! Don’t know if I can do it!

Israelis want you to bring hope on your trip. I am sure many Palestinians do, too. So many provocations, injustices, indignities to overcome! So many mistakes, miscalculations, squandered opportunities! So much hatred for the “ger,” the “other,” to move past. And to think we’re all half-siblings of the same patriarchal father…