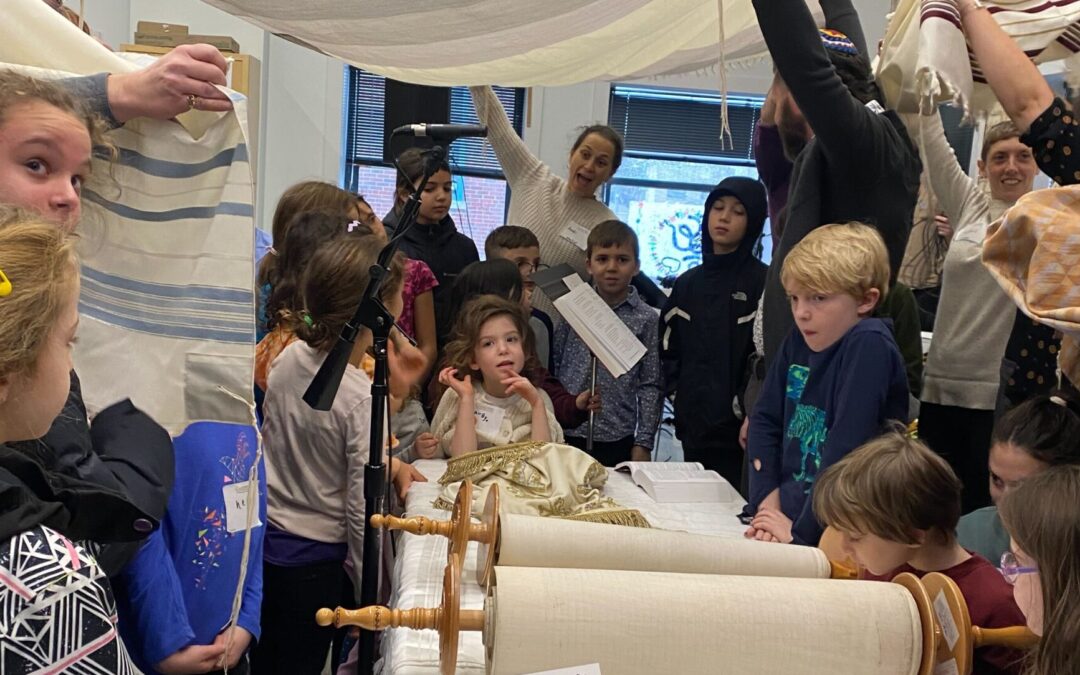

Our December 16th service was a Mensch Academy Student Showcase, an opportunity for caregivers and the Mishkan community to honor our students and their learning. Rabbi Steven took this opportunity to explain how we root our teaching philosophy in self-expression, community, honor, and inspiration.

****

Our parashah opens with a dream. Pharaoh is standing on the bank of the Nile, when seven cows emerge from the water – handsome and sturdy – to graze on the reeds. They are followed by seven more cows. But these are ugly, gaunt. And instead of grazing, they eat the seven healthy cows that preceded them. Pharaoh wakes up. What an unusual dream. He rolls over, falls asleep – and dreams again. This time he is in a field. Seven full ears of grain grow from a single stalk – but then close behind them, another stalk pushes through the soil. This one has seven ears of grain that are thin, scorched by the hot and dry eastern wind. Suddenly, the sickly ears of grain swallow up the robust ones that grew before them. Pharaoh wakes up.

I imagine that each dream, alone, would have struck Pharaoh as odd – but in the end forgettable. Yet the parallelism between the two was impossible to ignore. And so, agitated by what he has seen, Pharaoh sends for the best magicians, priests, and sages in Egypt. He tells them about these dreams but no one can offer a satisfactory explanation. Enter the hero of our story. Joseph (who has been languishing in an Egyptian prison for some time, during which he has gained a reputation as the dream interpreter par excellence) is invited to offer his explanation of these strange visions. They are one and the same, he tells Pharaoh, seven years of abundance will be followed by seven years of famine. Egypt best prepare during these years of plenty for the time when we will be without.

Given Joseph’s explanation, the symbolism of the cows and ears of grain seems obvious. So why did the magicians, priests, and sages of Egypt – the best of the best – struggle to interpret these dreams? A colleague of mine, Rabbi Zohar Atkins, pointed me to an insight offered by the Iturei Torah – a collection of Hasidic commentaries. Perhaps the reason they couldn’t find an explanation for Pharaoh’s dreams is that they defied the natural order. Cows don’t eat cows, and grain doesn’t swallow up grain. Joseph, however, is not constrained by the limits of their imagination. Why? R’Zohar offers that Joseph, who is a Jew and not an Egyptian, inherits a legacy of “narrative violation.” He explains: “From the perspective of ordinary consciousness, the existence of the Jewish people isn’t just an unlikely possibility, it is an absurd one.”

Think about our story so far. Joseph survives the impossible – abandonment by his family, forced migration to a foreign land, years of bondage – to be in the right place at the right time, setting him on a course that will lead to a position of a power that enables him to save the same brothers who sold him into slavery decades prior. He is among the youngest children of a second son, Jacob, who overturned the natural order to secure the birthright promised to elder brother. He is the grandson of Isaac, miraculously born to his parents Abraham and Sarah well into their old age.

And then after Joseph, the history of our people unfolds. We are miraculously liberated from slavery. We wander through an unforgiving wilderness for forty years. We build and rebuild (and then rebuild again) a nation in the land of Israel. We survive catastrophe after catastrophe, each time outliving those who sought to destroy us – and through it all, we are not merely surviving but thriving. Through discussion and debate, the rabbis lay the foundation for a spiritual and moral tradition that meets new obstacles, adapts, and improves. The result of this effort is us, here, in this room several millennia after Joseph sat at the foot of Pharaoh’s throne to interpret his dreams. The thing is, he was given the same text as everyone else: seven happy, healthy cows eaten by seven starving ones, seven robust ears of grain swallowed up by seven sickly ones. But rather than being limited to what was given (the words on the page, so to speak) Joseph’s imagination, fueled by his family’s – that is, our family’s – collective memory of the impossible becoming possible, allowed him to unlock a deeper meaning.

To respond to the perceived limitations of the world with creativity, optimism, and the understanding that what stands before us is not the only reality that is possible – this is the beating heart of our tradition, keeping it alive these thousands of years. Think about Hanukkah, which we just marked the end of last night. I’m sure you know the story of the oil: that when the Maccabees retook the temple and set about rededicating it to its sacred purpose, they could only find one cruse of oil – sufficient to light the menorah for one night. Yet somehow, it stretched through eight long nights, long enough for more oil to be made. Yes, this is a miracle. But more miraculous is that our ancestors responded to the impossibility of the moment by lighting the menorah in the first place, refusing to simply see things as they are – but embracing the possibility of what could be.

It is this ethos that underlies how we teach at Mishkan. I often tell folks that we don’t believe in a one-size-fits-all Judaism, because our tradition thrives in “narrative violation” – meeting the rote with the inspired, the ordinary with the creative, the expected with the unexpected. Celebrating our Mensch Academy showcase today (thank you to our students who stepped up to help lead service, and please check out the amazing learning they’ve been doing with the exhibition set up by our educators), I’m reminded of the guiding values that shape our children’s educational experience.

The first is hineini, self-expression. We meet each student, in their fullness of self, with love and welcome their thoughts, feelings, experiences, and needs – because their unique voice is a link in the chain of tradition that keeps Judaism strong, vital and relevant. We encourage agency in learning, allowing students to stretch beyond the perceived limitations of a text or topic to offer their own interpretations – something only they, in their individuality, could dream up.

The second is kehilah, community. Alongside welcoming each student’s whole self is being in a community that celebrates the fullness of others. We are each other’s best teachers and caretakers. Joseph could have used his skills as a dream interpreter solely for his benefit – yet he offers his services for the wellbeing of the whole nation, recognizing and embracing his place as part of a larger whole. Our students benefit from being part of a community where each individual offers their individual talents – and learns from that which others bring to the table.

The third is kavod, honor and dignity. By welcoming students’ ideas, experiences, and questions we create an environment where individuals feel safe enough, loved enough, and respected enough to take risks. To find the impossible within what is given as possible, to embrace our inheritance of “narrative violation,” we must know that there are people there to catch us when we fall. The Jewish people have never wandered alone. Every miracle of our history has been experienced in community.

And finally ruchaniyut, joyful inspiration. While our students are wrestling with Torah, or picking apart a prayer, or engaging in an activity – they are laughing, they are playing, and they are finding joy in what they do. I believe joy is what has sustained our people through a history struck through with tragedy. To create space for joy is not a denial of the difficulties we face, but a reminder that we are not only living – but living for something. It is the light of the hanukkiah against the darkness. It is the reckless abandon of Purim, in a world where anything and everything can change. It is the freedom to gather around the seder table, even as we continue to seek justice outside of our doors.

While these are the guiding values of the Mensch Academy, how we create space for our children to not only grow in their Jewishness but make it their own – they are also a roadmap to the inspired, down-to-earth Judaism that many of us come seeking at Mishkan. Hineini, kehilah, kavod, ruchaniyut – showing up as our whole selves, contributing to something bigger than what we could accomplish alone, taking risks, and finding joy: this is how we stretch beyond the limitations of what we had been taught is possible, and imagine something that had not been done, in this exact way or in this particular context, before. I hope you’ll be inspired by the learning that our students have been doing, and embody their spirit of creativity and courage. In a world that often tells us that this is just the way things are, I know we can dream bigger.